Supporting peacebuilders to meet the challenge of organised crime

On 13 November, the FBA starts its second round of International Expert Forums focusing on 21st Century Peacebuilding, together with the Centre for International Peace Operations, International Peace Institute, and SecDev Foundation. First in a series of four will be an event on organised crime, extremism, conflict and peacebuilding.

The event is important for two chief reasons. First, organised crime poses a massive challenge to development and peacebuilding goals. Similar to other transnational threats (terrorism, for example), organised crime and extremism can “trap” countries in cycles of insecurity, violence and poverty.

Second, organised crime is not a new phenomenon, but it has mainly been treated as a law enforcement problem. The nexus with peacebuilding has been overlooked. The meeting on 13 November brings together researchers, practitioners and policy makers under the basic premises of what works and what doesn’t, in order to identify action points for the future, for both researchers and policymakers.

Violence, organised crime and how we understand conflicts

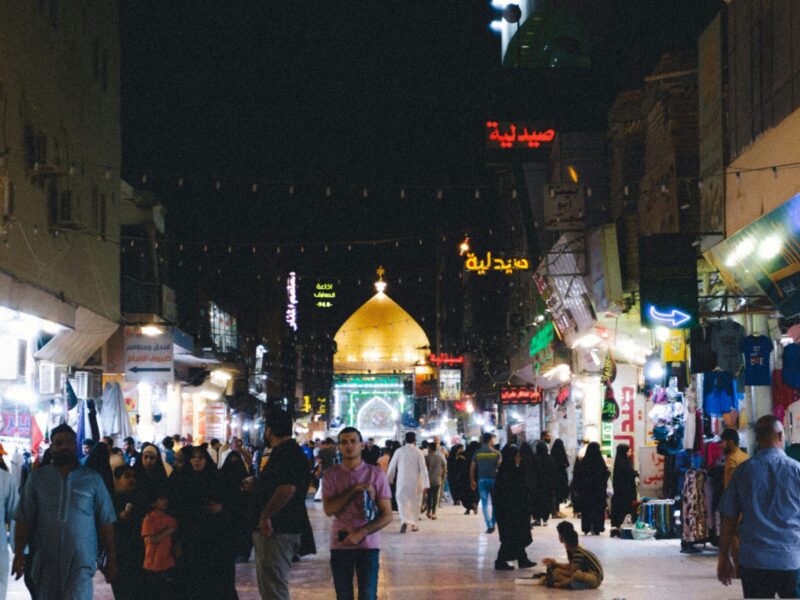

What does organised crime and extremism mean for individuals in conflict and fragile states? In a very simple and concrete way, it means that they live in a world where “the strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must”.[1] One deeply worrying example of this is the high level of homicides linked with organised crime, as shown in the data from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

While separating homicides and criminal activity from lethal violence in a conflict is not always easy, a significant amount of homicides in conflict countries are related to criminal activities. What’s more, homicides (to stick with that, though there are many other forms of violence, not least sexual and gender based) seem to be concentrated to capitals and cities. This, again, shows a link to conflict settings where urban areas typically receive an influx of internally displaced persons seeking refuge from fighting.

For the international community, the high level of lethal and non-lethal violence, and the increase of criminal activity in conflict settings, fundamentally challenge the somewhat static view on crisis and conflict. The typical bell curve of conflict (going from escalation to de-escalation of conflict) is largely inapt for capturing recurrent cycles of conflict, “frozen conflicts”, pockets of fragility, low intensity conflicts and stratified conflicts taking place at urban or sub-national levels. For individuals in most conflict affected states, peace is a temporary experience and conflict not a question of if, but when.

Many studies use the term 21st Century Conflicts – referring to the fact that far fewer civil wars are recorded (and also fewer battle related deaths). That may be the case, but then it is a very short 21st century we are dealing with, to paraphrase Hobsbawm[2], because conflicts are changing again due to the influence of organised crime and extremism, and deaths related to criminal activities are increasing.

What’s the link between organised crime and conflict, and what does it mean for peacebuilders?

There are many links between organised crime, conflict and fragile states. Fragile and conflict states have weak institutions exercising nominal control over the territory. The institutions are not only weak in terms of their capacity to deliver essential services, they are sometimes best described as following rule of lawlessness rather than rule of law, supporting, or engaging themselves, in criminal activities.

Combined with low level of public trust and confidence in the state, conflict and fragile states provide a perfect setting for organised crime and extremism in terms of means and opportunities – for the transit of drugs, people, and arms, for a chance to regroup and build capacity, recruit new members, and to diversify the methods of doing business. When organised crime gets a foothold in fragile and conflict states like Guinea Bissau, or in regions like the Mano River Basin, also in West Africa, it perpetuates a downward spiral of sapping state capacity, state legitimacy, and public trust.

There is no simple answer or silver bullet recommendation on how to effectively tackle organised crime in fragile and conflict settings. As an absolute minimum, however, it is abundantly clear that strategies must be based on broad coalitions, involving the development, security, and peacebuilding communities, as well as national and international law enforcement agencies and networks of cooperation.

It is also evident that more evidence is needed. We must scale up our efforts on mapping and understanding how organised crime operates, how it links to conflict in various forms (at international, national and subnational levels) and how it relates to other transnational threats, such as terrorism.

Lacking a more refined understanding, our current peacebuilding policies and practices will fall short, and peace will be just a brief, fragmented interval in societies plagued by criminal violence.

[1] “Melian Dialogue”, Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War.

[2] Eric Hobsbawm, Ages of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century 1914-1991.

av Richard Sannerholm