More than blue helmets needed

Right now a review of UN peace operations is taking place. The review looks at UN efforts to both keep and build peace, and it is long overdue – it’s been fifteen years since the last review was done and in our line of business, that is a long time considering that conflicts and crises change their ways.

While it is past due, there is also a risk that the review will miss the mark by being too much informed by past practices. Peace operations have repeatedly proven their value in a number of conflicts, but they are also blunt, inflexible and costly instruments.

Moreover, the international system for managing conflicts and for maintaining peace and security is in many respects outdated, primarily attending to civil wars in resource weak countries. This is not the full story of what crisis and conflict looks like in today’s world, and between the ‘typical’ civil war and the threat that people face in ‘untypical’ conflicts, falls the shadow. Thus, while there are high expectations that the review will manage to modernise peace operations it does not mean that peace operations will be more capable of handling modern conflicts.

Conflicts pasts

There are sixteen ongoing UN peace operations. Nine of these are in Africa. The peace operations in Africa are the largest in terms of personnel (military and civilian). They are also, typically, long running missions hosted in countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia and the Central African Republic. Outside Africa, the UN operation in Haiti bears the most resemblance in terms of costs, personnel and mandate.

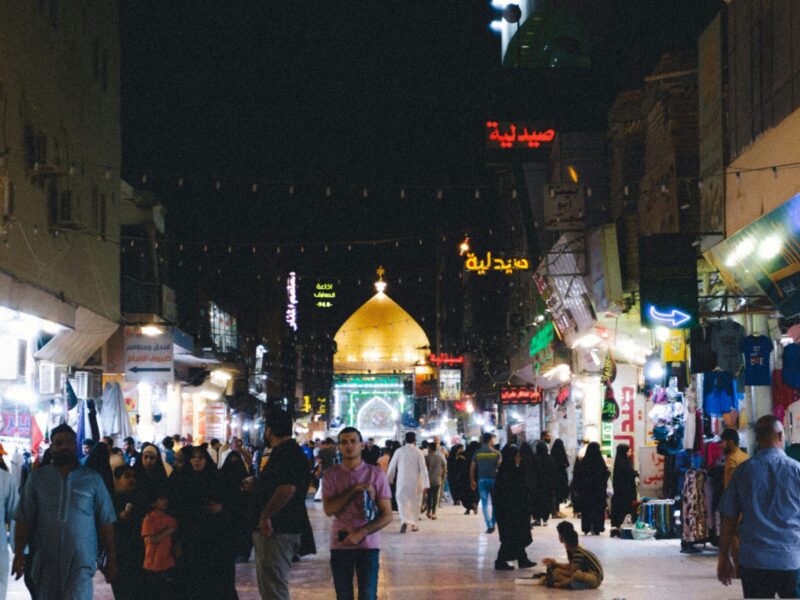

The remaining five peace operations are, in some respects, relics from the cold war (though the cold war seems to be back in fashion again), for instance the UN missions in Kashmir, Cyprus, and Middle East. In parallel with peacekeeping operations, there are also eleven special political missions. Six of these are in Africa.

There is a big difference between where UN peace operations are deployed and where conflicts take place. Think for example of Gaza, Syria, Nigeria, Philippines, Ukraine, Burma-Myanmar, Colombia, Georgia (South Ossetia and Abkhazia), Moldova (Transnistria), Armenia and Azerbaijan (Nagorno Karabakh).

Conflicts like these, some low intensive some high intensive, others civil wars and some wars between states (and some misguidedly called ‘frozen’), all affect negatively on the lives of ordinary people and communities. To this list we can add countries and places where criminal violence and transnational organised crime exert a huge toll on communities. Consider urban violence in different parts of Mexico, Guatemala City, and Kingston, or countries like Venezuela and Yemen where deep-seated political violence and instability borders large scale civil conflict. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime have a Global Homicide Book that is as informative as it is depressing when it comes to understanding situations where “the strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must” and to which there does not seem to be a silver bullet solution.

A square plug in a round hole

In the countries and places listed above, deploying a UN peacekeeping or a special political mission would be like fitting a square plug in a round hole. They are ill-suited to the complex political dynamics and intricate power-plays. Not only that, a large UN force would not be welcomed by either parties in most of these conflicts, and consent matters still to UN peace operations.

However, it is not just the UN. The EU, which tends to overlap (or piggyback) with UN peace operations, has repeatedly showed that it is incapable of responding to conflicts where a ‘mission style’ does not match the needs and demands.

The events following the Arab spring clearly revealed this – for instance, what Egypt or other countries in the region needed then was not an EU police mission, but technical assistance within a constructive framework of aid, trade and dialogue. The EU finally established a civilian border mission in Libya, which was both premature and overly ambitious at the same time.

Similarly in Ukraine. While failing the important task of keeping EU member states in check (thereby undermining the potential of a unified EU pressure on Russia and Putin), the EU has instead offered an SSR style police mission to Ukraine. This is not where the shoe hurts. Moreover, even if the shoe fits, it can still hurt. What Ukraine has been in need of, and is still in need of, is long-term economic assistance, support to political reforms, relaxation of visa rules, constructive pressure on fiscal discipline and governance reforms with a clear end objective in sight.

The future is now

There is a risk that past conflicts will inform future response and readiness. If peace operations as we know them continue to form the backbone of UN’s mandate to maintain peace and security, the maintenance of peace and security will become obsolete and cater to a certain kind of conflicts while neglecting others where the demand don’t match the supply.

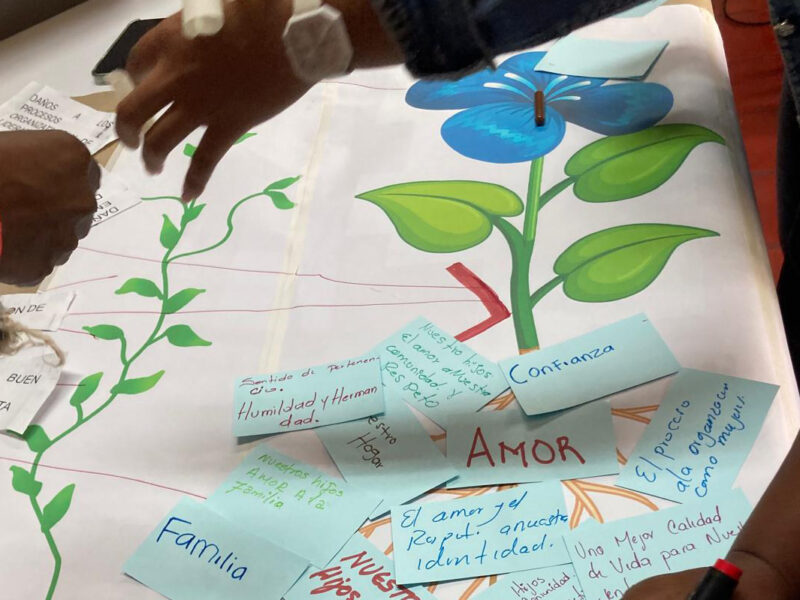

Responding to the many different conflicts of today and tomorrow is not just about keeping peace, or peace building by the ‘usual suspects’. The Venice Commission played a key role in constitutional reform processes following the Arab spring, notably in Tunisia, where more traditional donors and actors could not. The Venice Commission is known for its subtle yet highly sought after technical expertise that can be provided in a constructive participatory process. International NGOs, transnational corporations and professional networks such as bar associations, for example, are already engaged in different ways in conflict and crisis settings, bringing with them innovative ways of conflict resolution and peacebuilding.

Moreover, the leverage of international and regional organisations for keeping and building peace is also not something that should be taken as a given. In retrospect we might find that Standard and Poors’ or Moody’s credit ratings for Russia did more for peace than any EU sanctions or heavy handed EU missions ever did.

What does this mean for the UN and the review of peace operations? One thing is clear: for the UN to be able to shoulder the responsibility of maintaining peace and security, it has to make use of its whole array of departments, funds and agencies, in particular in non-traditional settings with organised crime or political violence, and where a UN mission is neither needed nor wanted. It also means a doubling-down on efforts to better link peacekeeping, peacebuilding and development actors together, and to include and build partnerships with non-traditional actors – making sure that the plug fits the hole.

av Richard Sannerholm